|

|

|

|

| Low-Level Photography Reports My article for AFM: Hellenic Flying - Fast and Low! |

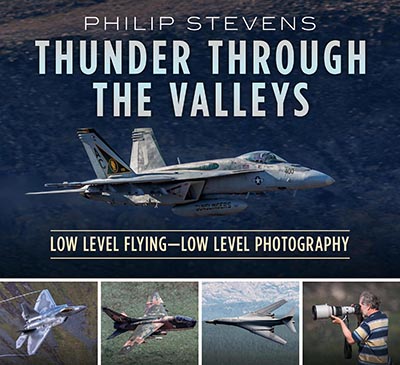

| Low-Level Flying Photography 'Thunder Through the Valleys' |

Philip Stevens writes for Aviation News on low level flying to promote his new book; Thunder Through the Valleys: Low Level Flying - Low Level Photography.

Philip Stevens writes for Aviation News on low level flying to promote his new book; Thunder Through the Valleys: Low Level Flying - Low Level Photography.It's an awe-inspiring sight to see a fighter jet roaring through a valley at low level. Philip Stevens provides aircrew insights from the RAF, Hellenic Air Force and USAF on the skills, procedures and continuing necessity for low-level flying. The RAF continues to teach student pilots to fly at low level, starting with the Grob G115E Tutor T1 - which is currently being replaced by the G120TP Prefect T1. As new aircrew progress through the fast jet training 'pipeline' they undertake sorties involving low level on the Shorts Tucano T1 (soon to be superseded by the Beechcraft T-6C Texan T1) and BAE Systems Hawk T2 before moving on to a frontline type. Progressive training and regular practice is essential if the skills required for this demanding type of flying are be retained and employed during operational missions. An experienced Tornado GR4 pilot said: "The actual flying is relatively easy. Like driving a car, you just get used to it - you don't think about it. "During pilot training you build up the speeds [Tutor 120kts, Tucano 240kts and Hawk 420kts] while reducing the height. We fly at seven miles a minute which now feels comfortable. You build up your capacity by doing it repeatedly. Flying at low level becomes automatic, giving you time to think about the bigger picture such as gliding sites, aerials, the weather ahead, where the other aircraft is, the next turn and your fuel level." |

|

| A regular sight at low level in the UK has been the Tornado GR1/4, the RAF is due to retire the bomber on March 31 next year. |

|

| Greece ordered 36 F-4E Phantom IIs in 1972 and a further 18 four years later. By 1979 all had been delivered. All Hellenic Air Force fast jet aircrew are trained to fly at low level. |

| STAY LOW, STAY SAFE While some in military air arms view low-level tactics as outdated and from the Cold War era, Tim Davies believes they're still relevant today. Indeed, he takes the view 'stay low, stay safe' to avoid being detected by the enemy and reduce the chance of coming under attack. RAF Tornado pilots practise flying as low as 100ft above ground level (AGL) as part of operational low flying (OLF) training. Planning is meticulous and flying these types of sorties is very demanding. Sqn Ldr Keith Woodsford, a former IX(B) Sqn pilot, explained: "The lower you go the more the pilot must concentrate on flying the aircraft. The first time [is] a complete adrenaline rush, which you must dumb down to free up your capacity." He added: "The RAF syllabus for OLF training is that it's first flown as a single jet, then as a two-ship and then a four-ship. For an OLF crew the pilot's focus is not to hit the ground and to terrain-hug as much as possible. "You're doing OLF for a reason - to minimise your radar pick-ups during target ingress or egress. Flying at between 100ft and 200ft you focus on 45° each side of the nose and make sure you're flying as accurately as possible." Currently on exchange with the US Navy, Sqn Ldr Woodsford compared OLF training in a two-seat Tornado GR4 with the single-seat F/A-18E Super Hornet: "You can't fly that low in a single-seat F/A-18E and perform the same tasks as well, so we fly more between 200 and 500ft." Recalling the terrain following radar (TFR) on the Tornado, he said: "TFR was used at night or in poor weather. You could also have [it on] while manually flying so that it would not feed in to the autopilot but still go to the flight director dot in the cockpit. If our velocity vector was on or above the flight director dot, you would manually avoid the terrain ahead. "An issue with the TFR is the 'g' limits: it utilises a lot less than we could use manually, so I can terrain mask more effectively flying manually. If it was a nice clear sky at night on my NVGs I would disengage the TFR from the autopilot and fly manually. We still had a TFR display in the cockpit, so I can still see if my jet is going to encroach my MSD [Minimum Separation Distance - a set distance all around the aircraft where all terrain and obstacles must be avoided]. I can delay my manoeuvre to be more aggressive with the jet. "At 100ft, if you lose concentration it's just over a second before you impact the ground if it's flat - and that doesn't take into account rising terrain ahead of you. An OLF sortie is meticulously planned before the flight, noting the sides of the valleys you'll be belly-up to on the way through." |

|

| A Hellenic Air Force F-16C Block 52 Fighting Falcon, fitted with conformal fuel tanks, makes a tight turn at low level. |

| CURRENCIES, PROFICIENCIES AND RULES It's accepted that low-level flying skills are perishable. Sqn Ldr Steven Beardmore, Tornado GR4 standards and evaluation, of RAF Marham's Operations Wing stated: "If you don't practise at low level then it could become a very dangerous environment. The need is there to keep our guys current and make sure they're safe in how they operate. "Pilots who've not flown [at low level] for 31 days will have a check ride. If it's over two months since [they] flew at low level, then recertification is required." He described the process: "They must gradually work down to the extreme low level required. Another pilot will fly on a check ride [in the rear seat] to make sure their skill sets are up to standard before they go out with a WSO [weapons systems operator]. Pilots have various check rides in a year including an annual one.

"It's important to monitor their handling skills in the low-level environment. Many hours are flown each year at low level in the UK: to do this safely it must be tightly controlled and managed." Tim Davies agrees: "Low-level flying is an unforgiving business and it doesn't take much to get it wrong. Therefore, we have currencies, proficiencies and rules to make sure that we're safe to operate when close to the ground." Sqn Ldr Hale, Officer Commanding Low Flying Operations, based at RAF Wittering in Cambridgeshire, said: "Every effort is made to keep the low-fly system safe and to disturb the public a little as possible. Our aim is for aircraft operating at low level to be co-ordinated, deconflicted and separated, day and night. To reduce noise pollution, we set minimum altitudes and maximum speeds. the use of afterburners is restricted." Reheat is prohibited at low level except for essential training requirements, aircraft emergencies or authorised displays." Wg Cdr Challen, a former OC Marham's Operations Wing, explained: "We must be flexible to avoid flying the same routes each day and [over] special public events," adding: "Politicians decide where our military forces should be sent in times of conflict. It's both important and reasonable that aircrew are properly trained for the life-threatening environments they are sent to."" Each NATO country has its own rules and procedures for low flying. To improve standards and increase experience, their air forces can undertake training over unfamiliar terrain in other alliance nations. LOW-LEVEL FLYING IN GREECE In April, the Hellenic Air Force held its annual Exercise Iniochos at Andravida Air Base (AB). Participants included the RAF's 3(F) Sqn, flying Eurofighter Typhoonsand the USAF's 492nd Fighter Squadron (FS) from the 48th Fighter Wing (FW), with Boeing F-15E Strike Eagles. Sorties with Hellenic Air Force (Elliniki Polemiki Aeroporia - HAF) units featured roles ranging from air-to-air combat to strikes against sea and land-based targets. Many of the missions involved low flying, with participating units briefed at the beginning of the exercise on the rules and procedures for such operations in Greece. All HAF fast jet squadrons train to fly at low level through vast mountain ranges across Greece or over the Aegean Sea. Capt Eftichiadis Eftichios, an F-16C/D Block 52+ Fighting Falcon instructor pilot with 337 Mira, said: "The terrain in Greece is very diverse and so ideal for low-level flying training - it has many high mountains and deep valleys as well as large areas of sea."

Greece's fast jet pilots can train down to 300ft, provided they avoid restricted areas such as tourist beaches and archaeological sites. Cities and towns have to be overflown at a minimum of 3,000ft AGL. Very Low Flight (VLF) areas, set aside for this type of training and sited over land and sea, are where military pilots can practise low-level interceptions and evasion manoeuvres with fewer restrictions. All squadrons within the Hellenic Tactical Air Force (HTAF) Command are issued a set of pre-planned sorties called combat profile missions (CPMs). Each one is in a booklet with a unique number - for example, CPM725N - and they enhance safety by reducing the risk of mid-air collisions. Air traffic controllers are aware of CPM numbers, which a pilot can refer to en route. The CPMs are used daily for low-flying training with routes through mountain valleys, while others are plotted over flat land or the sea. This enables pilots to practise navigation and terrain masking, though CPM routes are not for low-level interception or evasion exercises. Lt Col Avraam Kazantzoglou, a former 338 Mira squadron commander at Andravida with 2,000-plus hours on the McDonnell Douglas F-4E (AUP) Phantom II, said crews are not restricted to using the pre-planned CPMs. "If I need to see how effective the pilot or flight leader is I can create a different missionand this is added to the next day's flying programme." An area of airspace will be reserved which might be as large as 150 miles (241km) by 80 miles (129km) over land and/or sea. Twelve hours' notice must be given to book such a sortie, in which a flight commander can freely manoeuvre his aircraft or formation to respond to a 'hostile' aircraft. For exercises such as Iniochos, the standard CPMs are not used - different routes are created across Greece for diverse targets to be designated by the mission planners. There are no one-way valleys, as in the United Kingdom Low Flying System (UKLFS) -established to reduce the chance of collision in busy areas - and Greek pilots fly on the basis of 'see and avoid' (as does the RAF) to make sure they don't get too close to other military or civilian aircraft. HTAF headquarters at Larissa Air Base monitors and controls all low-level flights, warning if necessary of any conflicts. As a double-check, air bases contact each other to make sure their flying programmes, worked out the day before, do not overlap. Flights planned at shorter notice, perhaps as little one hour before take-off, are still sent through to HTAF, which will check if there's any conflicting traffic. If so, the aircrew can offer to re-time their sortie or submit a new route. |

|

| This 338 Mira F-4E(AUP) is at low level in the Peloponnese mountains. Low-level strike is this squadron's primary role with 60% of sorties down to 300ft. |

| TERRAIN MASKING "Low-level flying is a skill not easily learned or retained - it requires regular practise using proven techniques and procedures that evolved over time," says Capt Eftichios. He describes the cockpit routine when flying fast and low: "You should focus on the near rocks, then the far ones, to plan ahead; then check six [look behind] for your mate, then look at the instruments and HUD. It's a circular motion around the cockpit."

Adding to the challenges, it's common, where the ground lacks features, to lose focus of the horizon especially when flying over the sea. When pilots reach their first HAF squadron for conversion training to a frontline aircraft type they are taught low-level terrain masking - as opposed to terrain following techniques learned previously. With the latter, an aircraft will pass over a rise in the ground in level flight, which will incur negative 'g'. For terrain masking, pilots avoid flying over mountains, instead flying either side of the summits to take advantage of the blind sectors where ground-based air defences and radar cannot see their aircraft.

The technique to cross a ridge is to pull up and pass over the crest almost inverted at 135°, with positive 'g'and push the nose down while reducing thrust in the descent on the other side to maintain the speed required for the mission. This reduces, by three or four times, the period the jet is 'sky-lined' above a ridge - lowering the chance of being detected by the scan of an enemy radar from either the ground or the air. Pilots in pursuit of a low-flying aircraft employing terrain masking are often unable to lock-on with air-to-air missiles due to their systems being confused by the ground. For example, heat-seeking missiles can have difficulties because of increased humidity close to the surface. Humidity can also make it difficult to see the horizon over the Aegean Sea and can sometimes lead a pilot to drop the nose and quickly go below the minimum height. Flying under a very low cloud base also has its challenges. Capt Eftichios admitted: "In the 1990s a number of aircraft were lost due to them being 'closed in by the weather' because of low cloud, which did not give the pilot a way outand they failed to execute the correct procedure." Air Tactics Centre Commander Colonel Dimitrios Panagiotopoulos described another ever-present risk at low level - bird strike. When flying at 250ft over the sea in a Lockheed F-104 Starfighter, he saw a 'black ball' followed instantly by a deafening noise as the cockpit glass shattered in front of him. "The head of the bird hit me on the side of the helmet." He had his visor down, "but the shattered glass was like sugar - it went in my eyes and I could see nothing for a few moments. My first reaction was to come out of the turn and climb smoothly to high level." Barely able to see his flight leader he was guided to the nearest airfield on the island of Lemnos and talked down to the runway. "On landing I went to switch off the radio and found the head of the bird in the cockpit: it was a big seagull. I went to hospital, but was flying again two weeks later." |

|

| A 338 Mira F-4E(AUP) passing through a vast tree-lined valley deep in the Peloponnese mountains. |

| F-22As AT LOW-LEVEL In April 2016, 12 Lockheed Martin F-22A Raptors arrived at the home of the 48th FW at RAF Lakenheath, Suffolk, to work with RAF aircraft and the resident F-15C Eagles and F-15E Strike Eagles. Two F-22As flew a sortie in LFA 7, which included the Machynlleth Loop, accompanied by a pair of F-15Es and an F-15C. The 95th FS had deployed from Tyndall AFB in Florida, whose assistant director of operations, Maj Michael 'Deep' Frye (an F-22A instructor pilot), described the sortie: "Flying the Mach Loop was a unique opportunity to hone our low-level proficiency in mountainous terrain, which is something we don't have the capability to train for at our home station in Florida. "Many pilots in the 95th FS have previous experience operating on the ranges in the Western US and Alaska, which are quite like Wales. Flying a Raptor through the Mach Loop is no different than any other fast jet in the low-level arena: it requires significant mission planning and a spot-on cross-check to mitigate the inherent risks of tactical manoeuvring close to the ground. This low-level mission provided us the unique opportunity to practise tactical manoeuvring within the low-altitude structure." For the F-22A pilots involved, a higher level of mission planning was required to fly this low-level sortie in Wales due to their unfamiliarity with the terrain, the weather and the procedures required by the UKLFS. Most of the mission planning day was spent building the low-flying route and abort procedures, map construction including NOTAMs and bird and noise avoidance areas as well as calculating the fuel required. Aircrew of the Lakenheath-based 48th FW are familiar with flying at low level within the UKLFSand so were able to offer advice. "As a result of the mission planning process and leveraging of the experience of our local experts [48th FW pilots], the execution of the mission went off without a hitch," said Maj Frye. Raptor pilots are unable to discuss their tactics but will admit they must be able to operate in the full flight envelope available to them. Whether it's at high altitudes or low level, a pilot must be comfortable with his environment. Consequently, all Raptor pilots maintain a low-level currency down to 500ft which requires periodic flights at that height. |

|

| An F-22A in the Mach Loop - one of two that undertook a low-level training sortie in Wales along with F-15s from the 48th FW in April 2016. Raptor pilots train to ensure they are proficient at all levels. |

|

Although the 95th FS typically flies at low level over water near Tyndall AFB, it's also an important fighter pilot skill to operate safely over land with the extra complications it presents. Maj Frye described the increased skills required when flying at low altitude: "These training flights highlight the differences required in intercept geometry, the increased performance of the F-22and the dangers associated with low-level flying such as high 'g' onset rates, sustained 'g' loads and decreased time-to-impact." The Raptor handles no differently at low level than at higher altitudes, explained Maj Frye: "The integrated digital flight control system of the F-22 constantly attempts to maintain the same handling characteristics regardless of airspeed and altitude, relying on both the combined 70,000lb of thrust from the Pratt & Whitney engines and thrust vectoring." He added: "Any fighter pilot knows that manoeuvring in relation to the bandit is essential to survival... in this case the highest threat 'bandit' is the ground. The USAF has a multitude of instructions, regulations and training rules that are in place to keep us safe, especially in the low-altitude environment. "As you can imagine, the speeds and altitudes at which we fly may require 'aggressive' turns, within our manoeuvre limitations, to stay on route and ensure terrain clearance." Referring to the lessons learned during the deployment, he said: "While flying the F-22 is no different here than anywhere else in the world, the uniqueness of fighter integration with our NATO allies is what provides the greatest training value." The F-22A Raptor is one of the most advanced fast jets in the world, designed with stealth characteristics and utilising advanced weaponry and sensors. Even with all these capabilities, the USAF, like many other air forces, still sees the value in keeping aircrew proficient in low-level flying so they are prepared for all eventualities. |

Philip Stevens when researching for his new book; Thunder Through the Valleys: Low Level Flying - Low Level Photography, which discusses military low-level flying, has interviewed air crew from a number of air forces. His aim was to describe the; skills, dangers and procedures involved in flying an aircraft fast and low to avoid Radar detection and deliver munitions. He also wanted to discuss their missions and find out why aircrew are still trained to fly low despite stealth technology rendering aircraft invisible to Radar and smart weapons which are effectively delivered at medium and high flight levels. Pilots describe their most memorable low flying experiences, from their initial training to when in actual combat. What follows is an introduction to 'Thunder through the valleys' and includes some extracts from the book.

Philip Stevens when researching for his new book; Thunder Through the Valleys: Low Level Flying - Low Level Photography, which discusses military low-level flying, has interviewed air crew from a number of air forces. His aim was to describe the; skills, dangers and procedures involved in flying an aircraft fast and low to avoid Radar detection and deliver munitions. He also wanted to discuss their missions and find out why aircrew are still trained to fly low despite stealth technology rendering aircraft invisible to Radar and smart weapons which are effectively delivered at medium and high flight levels. Pilots describe their most memorable low flying experiences, from their initial training to when in actual combat. What follows is an introduction to 'Thunder through the valleys' and includes some extracts from the book.The information for this article comes from a new book, Thunder Through the Valleys: Low Level Flying - Low Level Photography by the author of this feature, Philip Stevens. The book's main focus is on the skills, reasons, missions, procedures and challenges from a pilot's perspective. The author also discusses how he achieved the stunning images in the book. Some of the types featured are the A-7 Corsair II, F-4 Phantom II, Tucano, Tornado, Sk 60, B-1B Lancer, F-16 Fighting Falcon, F/A-18 Super Hornet and F-22A Raptor. Aircrew with years of experience give fascinating insights into low-level flying and some of their most memorable sorties. Published by Fonthill Media ISBN: 978-1-78155-724-2 Size: 225 x 248 mm Binding: Paperback Extent: 128 pages Illustrations: 187 colour. |